Writing a Murder Mystery 101: Theory

This part one of a multi-part review of my own experiences and reflections writing a genre-focused murder mystery for publication. Pre-order the novel here.

Context

I’m in the final stages of writing my third book which is a murder mystery. I am by no means an expert on the subject, but during this process I learned a great deal and did a lot of study on the way murder mysteries are told. My previous two novel projects were much less commercial: one was an LGBT coming of age story and the other was a pensive, experimental literary piece.

Completing those works, though, freed me up to focus more on story. Rather than wrestling with complex emotional and psychological issues, my creative energy wanted to play with plot, character, romance, and murder (the fun, Britishy, off-camera kind, not the Slashery, violent, more American style).

I give that context merely to say that my observations here are focused on commercial content, not literary fiction. That is not to discount the literary merits of the works I’m exemplifying below but merely to say I wasn’t looking to write a deep, complex psychological work that investigates the motives of a killer — I wanted to sell books. Below I’ve broken out 3 (and one-half) key items that I think are really valuable concepts in thinking about how to construct a mystery. The examples I am using below are taken from Agatha Christie and a few others. Ms. Christie, as the best-selling mystery author and regular author of all time (over 2 billion served), seemed like a great example to use.

Also, be warned that a great number of spoilers for her books, especially Death on the Nile are ahead.

Plot

Agatha Christie is a plot genius. Very often in literary critiques individuals will say “her characters are wooden, and the writing is sparse, but the plot — my god — the plot!” (For more on this check out Sophie Hannah’s video.)

As with any genius, the structure and materials she works with aren’t anything extraordinary. She relies heavily on the three-act structure that dates all the way back to Aristotle and is used in everything from TV shows, screenplays, novels, and opera. But! Her use of the structure, especially twist endings is extraordinary.

In terms of plot analysis, Death on the Nile is a great example of the master at work. Essentially, the breakdown looks like this:

- Act I: Setup — Introduction to characters, setting, background (Chapters 1–10)

- End of Act I event — Linnet’s escape from a murder attempt

- Act II: Confrontation — Shiz gets real (Chapters 11–22)

- Novel Midpoint — Murder of Linnet

- End of Act II Event — Louise is found dead

- Act III: Resolution — Things wrap up (Chapters 23–31)

- Act III Event — Murder of Mrs. Otterbourne

- Novel Climax — Murder/Suicide

If you’ve ever studied structure before, you know that the major gear changes are necessary to keep the reader deeply involved (Act I event, Act II midpoint, Act II event, Act III Event, Climax). Most anything you read or watch will have these tectonic shifts to drive you forward in the narrative.

At the same time that Ms. Christie is giving these macro changes and plot developments to drive action forward, she’s also giving us micro events that drive narrative at the chapter level. If you read through a summary of the text, you’ll note that not a lot happens from chapter to chapter, but the breadcrumbs she leaves as you journey from one to the next ratchet up tension slightly. These can be new clues, a reveal, a shocking turn of phrase, really anything that piques interest from one chapter to the next.

To really keep the narrative firing on all cylinders, the plot has to be working at both the macro and micro levels with key events creating major ripples and small hooks between chapters sparking interest from page to page.

(Bonus: In Ms. Christie’s Crooked House, one of the main characters mentions murder story structure in the middle of the novel! The meta brilliance!)

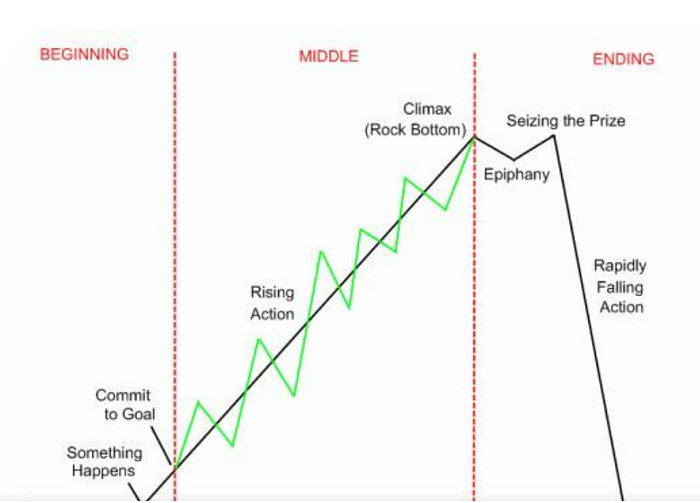

As a last aside, one of my super talented teachers from my MFA program Shauna Seliy drew a chart. I attempted to draw one digitally but… it didn’t work out; it’s wonderful that artsy Chica on Pinterest did the work for everyone:

The reason I like this graph more than standard plot graphs is that it shows the slight “heartbeat” of narrative events that bring up the tension. These small events lift the momentum slightly through the course of the narrative, while the macro structural plot events cause large shifts in momentum.

To mix mediums, the plot structure of Breaking Bad is a master class in this kind of plot development. Each season ratchets up tension from episode to episode, but then each season finale blows the entire conflict structure up an entire level. (And, tbh, if you’re looking at how to do anything, whether it’s plot, irony, character development, etc. … you can pretty much look to Breaking Bad.)

Characters

I like to highlight characters because in murder mysteries their use in the narrative is unique. Generally, the sleuths are highly memorable (Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple) while the other characters fill out as “types.”

Once again, in Death on the Nile, you get a general cast list of several classic archetypes of individuals:

- Linnet — the beautiful socialite

- Jackie — the scorned lover

- Simon — the dumb “jock”

- Pennington — the lawyer par excellence

Another great example of this is Clue. You simply have to hear the name of one of the characters and an entire persona forms: Miss Peacock, Colonel Mustard, Miss Scarlet, etc.

In murder mysteries, this is crucial, because by giving the reader a general form that they are comfortable with, they feel that they can then start reading between the lines more quickly.

Many actually critique the value of Christie’s works based on her not digging into complexity of character, but I would argue that misses the entire point of the work. Even real detectives usually rely on tropes — scorned lovers, greedy individuals who stand to gain — to start their lines of inquiry. Where Christie leans into complexity is the “secret” that most of her characters carry with them. Although they are types with (mostly) a single dimension, many of the characters harbor some twist which renders them more complex. Again, from Death on the Nile:

- Salome Otterbourne — pompous author, with a secret problem with alcohol

- Marie Van Schuyler — pompous socialite, with kleptomaniacal tendencies

- Mr. Ferguson — pompous student and Communist, who is secretly a Lord

- *Yes, so much pomposity

The collision of stereotype with odd tendencies, makes all the characters, if not complex, then, at least interesting. As a reader, this allows you to both know the character immediately and also see the discrepancies that may make them a part of the crime.

I would argue that another layer of Christie’s brilliance is how quickly she can build these characters. With a few lines of dialogue and a two-sentence description, she paints the picture and the reader is “in” on who they are. This allows the reader to transition from passive reader to active “detective” on the crime very quickly.

Reveals v. Twists

Of course, it would be remiss to not include Christie’s brilliant use of twists in an analysis of her work. I would actually argue that there is a bit more nuance to it than simply a “twist” — I think she uses two different methods to get that amazing “Aha!” out of readers. An insightful overview of plot twists is in wikipedia, including the fact that the first plot twist was from Arabian Nights as… wait for it… part of a murder mystery!

The Reveal

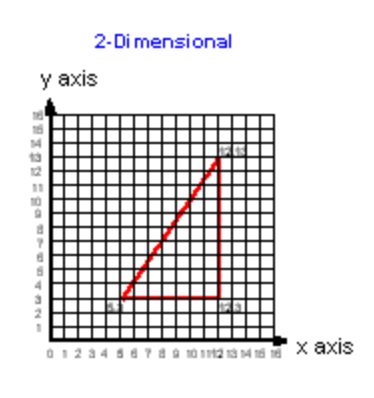

Reveals are what I believe most of us think of when we think of twists — these are where the “dots” of the narrative come together to form a surprise revelation, an “image” at the story’s climax that we may not have seen coming. I think of these as dots that form throughout the narrative on an X/Y axis. Before the conclusion, we see the image that the story has built for us (in the case below, a delightful triangle).

I would argue that Death on the Nile is a reveal. This is where there is enough narrative information and guidance to get us to the revelation of the killer before Poirot tells us himself. Every Scooby-Doo episode uses this structure to get the gang to the solution.

The Twist

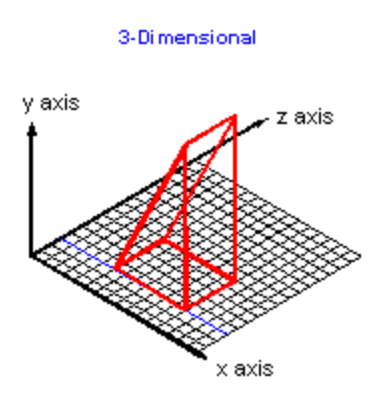

The twist is a level up from the reveal (its final form, if you will). The twist is an ending done so masterfully that, not only do we see an image at the story’s conclusion, but we realize that there is not only an X and Y axis but also a Z. Twists fundamentally change our perspective on the entire story and bring us some outside understanding we probably wouldn’t realize on our own (like realizing the triangle you thought saw you was actually a cheese wedge).

Christie’s most famous work, Murder on the Orient Express, utilizes this. She fundamentally alters our expectations coming into a mystery novel. “It must be 1 person,” we think. But those expectations are subverted. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd also utilizes the twist to amazing effect, thwarting readers understanding of how we relate to ALL the characters in a mystery. (I just can’t spoil it for you. The novel Moriarty is another great example of this.)

I think one of the reasons that the Harry Potter series has been so wildly successful is that JK Rowling built a world that already exists with X,Y, and Z axes. The magic in the book means that readers have to be vigilant of any possibility within the text. I will NEVER forget as a fourteen-year-old reading the end of The Sorcerer’s Stone and realizing that Quirrell and Voldemort were fused. Like. DANNNNGGGG. The power of letting readers imagine an ending where it’s not one person but an infinite number of possibilities is really, pure brilliance.

Speaking of Magic

As with any great works of art, you can’t simply study them and be good at them. There is magic in them and a power that specific authors bring to their texts that can’t be studied or repeated. A great number of items intersect in Christie’s work that make them popular 100 years after the first Poirot novel was written. In addition to plot, characters, and twists, I also wanted to just bullet out a few masterful things that Christie does that, I believe, contribute to her success:

- Tone: For some reason a lot of adaptions of her work want to make Poirot super serious, but the texts themselves are ROMPS. There is a lot of humor and the stakes are low. Murders are part of the fabric; they are non-violent and … dare I say it? whimsical. Creating a world of mysteries where people can be detectives and escape without too much “reality” is a boon for many readers.

- Setting: In addition to painting characters with swift, broad strokes, Christie does this with her settings, too. It doesn’t take a lot of effort for her to conjure up grand images in very little space.

- Practice: Christie wrote A LOT. (The internet suggests at least 77 published works.) With that much time with pen to paper, her craft could only grow stronger and more refined. (I’m mostly putting this bullet point for myself, who struggled A LOT on my first go around in the murder mystery genre.)

Next Up

Well, this grew way to long, so I’m definitely glad I split it into multiple parts. The next part will be about my own effort in constructing a murder mystery — the practice. It will not at all be a “do this” but rather “I fell in this hole, avoid it.” We can’t all be Agathas, so, for those of us living in her shadow, it will hopefully provide some help in commiseration if you are working on your own pieces.

Tedd Hawks is a writer, trainer, and teacher from Chicago. You can follow his Instagram and humor blog.